In the nineteenth century Lough Neagh connected all of the North of Ireland via a series of Canals and River Navigations

These waterways were the Motorways of their day used mainly for transporting goods for import and export all over the counties of Ulster

There was also limited use by passenger services but this was soon superseeded by the railways.

At one time it was possible to travel from Coleraine to Limerick , Belfast, Dublin, or Waterford by Inland Navigation.

Blackstokes Bridge Benburb Gorge Ulster Canal

THE ULSTER CANAL

With the dawning

of this new millennium has come an awakening of the forgotten heritage

of a bygone canal age. The Inland Waterways Association of Ireland has

been successful in protecting the Shannon navigation, the Barrow

navigation, the Grand Canal and other associated waterways South of

the Border, and they with the Ulster Waterways Group, have managed to

put the case for the re-opening of the Ulster Canal, right to the top

of the cultural agenda. The task north of the Border seems so much

more difficult as we have virtually lost all of our historic canal

culture. Hopefully things will change, sooner rather than later. Half

of the Ulster Canal is in

Northern Ireland and half in the Republic. The partition of Ireland in

1921 did little to encourage any further investment in this exciting

project, perhaps today things are different, perhaps this is the

scheme on which to build co-operation, after all a linear waterway

threatens no one, but can benefit all.

The Ulster Canal opened in 1841 and linked the two major

expanses of water, Lough Neagh with Lough Erne. The original plan, as

now, was to create a navigable waterway, to link the ports of Belfast

and Coleraine with the River Shannon and onwards to Limerick or

Waterford. It could be argued the success of the Ulster Canal depended

on the completion of the Shannon Erne link, then known as the

Ballinamore and Ballyconnell Canal. This was opened to navigation in

1860, alas by the time it opened, the Ulster was virtually derelict.

The canal was then closed for major repairs but by the time it was

re-opened the Ballinamore and Ballyconnell Canal had all but been

abandoned. The improvements did bring a limited increase in traffic

but by the turn of the century the canal was again in decline. Thus

today, the shoe is on the other foot, to further enhance the success

of the Shannon Erne, we need to complete the missing link, we need to

re-open the Ulster Canal. The potential economic benefits for the

corridor are enormous, farm diversification, service industries,

tourism initiatives, the list is endless.

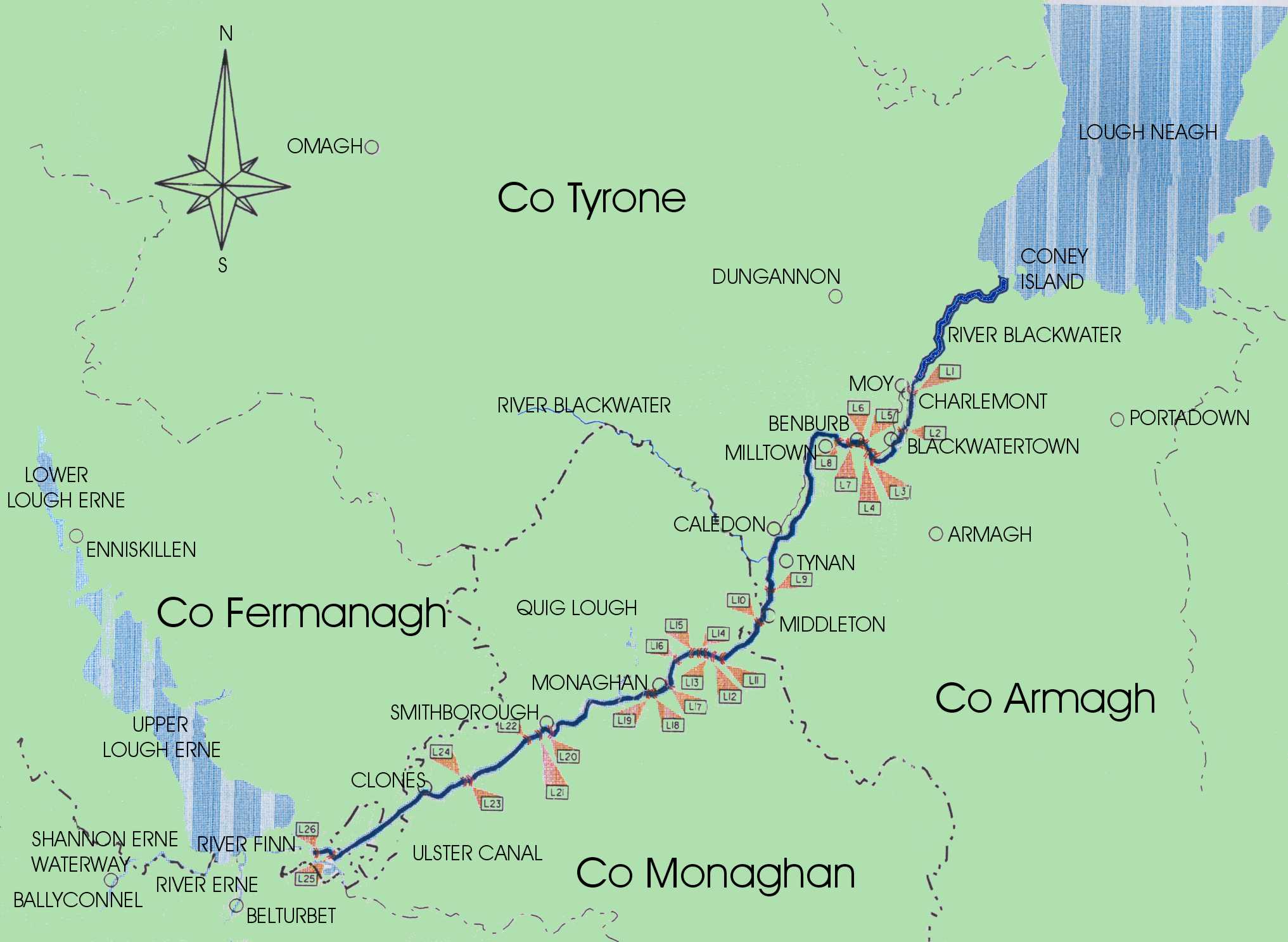

The canal is 46 miles long with 26 locks. It left the River Blackwater

just below the village of Moy and climbed through 19

locks to the summit on the far side of Monaghan, descending through 7

further locks, dropping down to the Finn River where it enters Lough

Erne near the Quivvy Waters. Shortly after leaving the Blackwater, the

canal ascended seven locks, through the Benburb gorge, arguably the

most spectacular yet the most difficult engineering and costly aspect

of the waterway, then on to its first border crossing at Middletown.

This stretch was one of the most picturesque stretches, journeying

through the estates of Lord Caledon, the Strong estate at Tynan Abbey

and the Leslie estate at Glaslough. The rise to Monaghan necessitated

the building of 7 locks in quite close succession; the canal then

skirted the town and headed for the village of Smithborough. Outside

Monaghan a feeder was constructed to create a water supply from a

small lake known locally as Quig Lough.

The canal then winds its way to Clones through some striking rural

countryside, then weaves in and out of the border four times before

its destination.

In

1794 the Lagan Canal had reached Lough Neagh and much

discussion ensued as to how to complete the infrastructure. Early in

the 19th century the engineer John Killaly, employed by the

Directors General of Inland Navigation was directed to investigate the

building of the link. Killaly had already worked on the Royal Canal,

built to link Dublin to the Shannon. His original proposals were to

build navigation with dimensions similar to those he had built on the

Royal. The total cost was to be in the region of £223,000, nearly

twice the original estimate. This seemed a strange proposal from

someone of the ability of Killaly as the proposed dimensions were some

18 inches narrower than the narrowest locks on the Lagan, Tyrone and

Newry navigations, thus to build a navigation not compatible with

those directly dependent on it, seemed a rather foolish proposition.

He also questioned if the water supply of Quig Lough would be adequate

and suggested deepening it, though this was never done. Despite much

local support the scheme did not see fruition for a further 13 years.

In the meantime financial wrangling put further pressures on the

proposals and what was eventually proposed was more like an exercise

in cost cutting. Projected returns were based on tonnages carried on

the Grand Canal, the most successful of the navigations. The original

contract had been given to a contractor named Henry Mullins and Mc

Mahon, they withdrew and the contract was awarded to William Dargan,

also known for contracts associated with the railways. Dargan was the

main contractor building the Kibeggan Branch of the Grand Canal, sad

to say Killaly would not see the fruits of his labours as he died in

1832, followed by Tedford a year later. Another engineer, William

Cubitt, perhaps better known for his association with railway building

was appointed to progress the scheme.

Whoever made the decision to reduce the lock size remains a mystery, in reality the width of the smallest lock, at the Lough Erne end of the navigation was 11ft 8ins. This meant cargoes being shipped from Belfast or Newry would have to be unloaded from one lighter to a different one to complete the journey. It is fair to say the first ten years of trading were disastrous, the fact cargoes had to change boats and the lack of water depth for the four summer months only proved it was going to be impossible to repay the loan. The Board of works assumed responsibility for the canal and eventually it was leased to its builder, William Dagan who was probably the main carrier. Faced with the threat of competition from the railways, Dargan transferred his lease to the Dundalk Navigation Company. In less than ten years the lease was again transferred back to the Board of Works. Again extensive work was required, by this time the Ballinamore to Ballyconnell navigation had opened and the directors were optimistic. It took eight years to carry out the necessary repairs, by this time the Ballyconnell navigation was impassable. Eventually the Lagan Navigation Company was persuaded to take control. It is fair to say moderate success was achieved but receipts would not cover expensive necessary maintenance mainly due to the lack of water. The Lagan Navigation Company was refused permission to abandon the navigation, but eventually it closed itself. The last lighter to sail the canal was in 1929 and the canal was officially abandoned in 1931 The majority of the stone for building the locks and bridges was quarried at Benburb and the bed of the canal was lined with puddle clay to ensure it was watertight. Regretfully the puddling was defective which meant the canal was not watertight, especially in the limestone gorge area at Benburb. The canal has some interesting aqueducts which remain intact today. These are at Caledon, Middletown, Clones and over the Finn River. One very striking feature of the waterway are the delightful lockkeepers’ cottages, all of which survive today in various forms of preservation. Today ownership of the canal bed in the Republic is in the hands of Monaghan County Council, whereas in N.Ireland it was sold to any farmers who wished to purchase their adjoining section. Regretfully approximately 10 miles of the original navigation have been filled in and some of the original hump backed bridges have been replaced with low level structures. Restoration is by no means an insurmountable task, indeed the surveys undertaken by the two Governments show it is a perfectly feasible project. The problems associated with the original navigation are relatively easy to overcome with modern engineering techniques, what then is the reason for the delay? The project depends on the will and commitment of the two governments, much of the required funding should be forthcoming from European and American sources, but the project needs a Political champion, sadly to date no one has had the courage to step forward. Here is a project that threatens none but benefits all, indeed it would inject resources into an area that has been starved of inward investment. The new cross border body set up to manage our waterways, Waterways Ireland, has within its brief the development of the Ulster Canal, all waterway enthusiasts await the day when again we can sail from Coleraine to Limerick.

The Coalisland Canal

Coalisland Canal Macks Bridge

The Coalisland navigation is one of the shorter waterways being about four and a half miles long. In conjunction with Ducarts Canal it linked the River Blackwater and Lough Neagh to the Tyrone Coalfields at Coalisland. Although short, it rises about 250 feet or 76 metres through seven locks and a series of dry hurries/wherries with quite an extensive basin at Coalisland. The distance of two and a half miles to the coalfields at Drumglass from Coalisland was fraught with difficulty. Tub boats were floated onto cradles and pulled by horses up the slope. Unfortunately this ambitious scheme was never really that successful. Sadly the Tyrone coal deposits proved to be of inferior quality and all too often coal was carried in the opposite direction. Despite the difficulties experienced the canal from Lough Neagh via the River Blackwater to Coalisland was a very successful enterprise with many thousands of tons of goods being carried by barge in both directions.

COALISLAND CANAL ENTRANCE BLACKWATER

Lagan Canal at Lisburn Island Centre

The Lagan Canal

The building of the Lagan Canal was

commenced in 1756 and within a year the first 6 miles from Belfast were

completed. Problems abounded, mostly of a financial nature; regretfully it

was to take a further 46 years to complete the project. The first engineer

was called Thomas Omer; he had first worked on the Newry navigation and

the project was completed by Richard Owen, an engineer who had worked on

the Liverpool and Leeds Canal. This was a successful waterway and carried

much freight during both the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Built to carry coal from the newly discovered coalfields of Tyrone to the

expanding port of Belfast, it more often carried fuel in the opposite

direction. It was finally abandoned in 1958.

Moneypennies Lock Newry Canal

The Newry Canal

The Newry Canal is the oldest summit canal in the United Kingdom. Built between 1731 and 1742 it linked the Irish Sea via the Newry Ship Canal and Lough Neagh, the largest fresh water lake in Western Europe. It was built to transport the

newly discovered coal near Coalisland to the merchants of Dublin. The pioneering engineer was a German immigrant called Richard Cassels

though he was replaced by an English engineer called Thomas Steers. This

was a successful navigation, Newry being the fourth most important port

in Ireland. Commodities carried included agricultural goods, tobacco,

timber, iron goods, whiskey and oil products. The railway, which runs

alongside the canal, was a factor in leading to its demise. The last

vessel to sail the canal was a pleasure yacht in 1937.

Thanks to Brian Cassells for contributing to these articles

created with

WordPress Website Builder .